The thickness of the PCB is among the most inherent in the design of the printed circuit boards and yet it is commonly accepted as a default instead of an engineering choice. As a matter of fact, thickness affects mechanical strength, signal integrity, thermal behavior, connector compatibility and manufacturability. No matter what size consumer device you are building or a large power industrial system, it is important to select the right PCB thickness to ensure long-life reliability and cost management.

What is PCB Thickness?

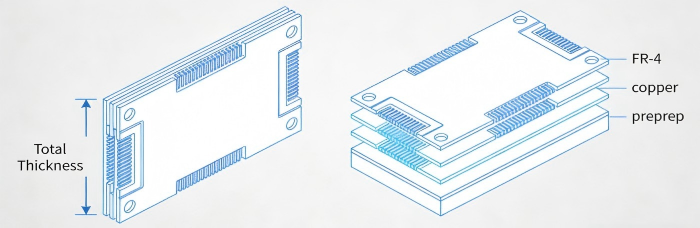

PCB thickness is defined as the cumulative completed distance between the top copper finish and the bottom copper finish. It consists of the body (generally FR-4), prepreg bonding materials, internal and external copper, solder mask, and the surface finish.

The PCB thickness of industry standard is 1.6 mm (0.062 inches). This value, which provides an ideal compromise between rigidity and weight, is the most commonly used, fits most through-hole part lead lengths, and is compatible with standard connectors and cases. Moreover, this thickness is well optimised in fabrication processes and material supply-chains, making it cost effective and reliable.

Nonetheless, PCB thickness need not be only 1.6 mm. Boards are usually between 0.2 and 3.2 mm or larger depending on the needs of an application.

Common Thickness Ranges and Uses

Various thicknesses are used in engineering requirements.

When boards are less than 0.6 mm, they are typically seen in ultra-compact devices like wearable products and smart modules, as well as some medical equipment. These designs give more emphasis on space and weight reduction. But thinner boards are less mechanically rigid and must be handled during assembly with care so as not to bend or warp.

Most consumer and industrial electronics are between 0.6 mm to 1.6 mm. This range is mechanically strong enough, has good electrical performance and is manufacturable. This type of board is multilayer, and is commonly used in communication equipment, embedded systems, and computing products.

Thick boards of over 1.6 mm are typically found in high-power, automotive, aerospace, or industrial control purposes. Greater thickness increases structural rigidity and mechanical stress and vibration resistance. It is also able to offer higher thermal mass which may be used to support power components and heat dissipation strategies.

What Determines PCB Thickness?

PCB thickness is not a choice of materials but a stack-up design. The first are the core substrate, prepreg layers, copper thickness, and the number of layers.

The structural basis of the PCB is the core. FR-4 is a fiberglass-reinforced epoxy laminate that is used in most stiff boards: it is flame resistant, its dielectric strength is high, and it is cost-effective. The thickness of the core is a significant factor in determining the size of the board.

Prepreg is a resin impregnated fiberglass sheet employed to bond the layers in the lamination process. In multilayer designs, dielectric spacing between copper layers is defined by prepreg thickness. This separation directly influences impedance, capacitance and signal integrity. Thus, any choice of thickness is required to be made with electrical performance concerns, particularly with high-speed or RF.

Typically the thickness of copper is given in ounces per square foot (e.g. 1 oz, 2 oz) which is also added to overall board thickness. Normal designs typically involve 1 oz copper. Applications with high currents might need 2 oz (or more) to add current carrying capacity and decrease resistive heat. But heavier copper also increases the complexity of etching and influences the trace geometry, thus a balance has to be maintained between manufacturing capacity and heavier copper.

Lastly, the number of layers affects the total thickness. The incorporation of signal layers, power planes, and ground planes adds height to stack-up. Nevertheless, additional layers do not imply a significantly thicker board. Even 6- or 8-layer PCBs can fit within a 1.6 mm profile when stack-up planning is employed.

Why PCB Thickness Matters

Mechanical Strength and Warpage

Rigidity is directly affected by thickness. The heavy boards are less prone to bending and vibration, hence suitable in rough conditions. Large or thin boards are more likely to warp, particularly when reflow soldering. Over bending may cause stress on the solder joints and lower the reliability of a product. Adequate thickness assists in dimensional stability during the manufacturing process and operation.

Signal Integrity and Impedance Control

In fast digital and RF designs, the thickness of the PCB is highly related to controlled impedance. The characteristic impedance is determined by dielectric thickness, trace width, copper thickness and material dielectric constant. Minor changes in thickness may result in an impedance difference, resulting in signal reflections, crosstalk or EMI. In such applications, thickness has to be designed as part of the overall stack-up design and not chosen separately.

Thermal Performance

PCBs with more thickness tend to have increased thermal mass, which then permits evenly distributed heat. This can be helpful in power electronics or power component designs. Nevertheless, copper planes, thermal vias, and the choice of material also have a significant role in thermal performance. Thickness does not ensure good heat dissipation, but should supplement a thermal plan.

Connection and Component Compatibility

Edge connectors and many others are made to fit standard 1.6 mm boards. The result of not adhering to this thickness without ensuring the mechanical specifications is poor mating or undue mechanical stress in the long run. Through-hole components are usually also optimized to standard board thicknesses. Before settling on thickness, mechanical compatibility should always be taken into account.

Manufacturing Considerations

The thickness of PCB directly affects fabrication and assembly. Board thickness makes drilling more difficult as aspect ratios become harder to plate through-holes. Adjusted pressure and curing profiles may be necessary in the lamination cycles. With copper designs that are heavier, more control is required during etching. In the assembly, thick boards dissipate more heat and might need modified soldering settings.

Non-standard thickness may raise production cost and lead time when it involves special processing or where it involves special materials. Evidently, prior communication with the PCB manufacturer assists in making sure the thickness of the chosen choice is matched to the manufacturing capacities.

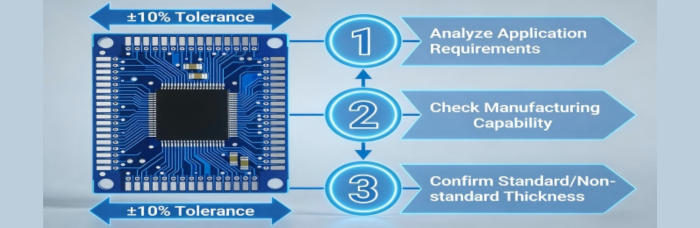

Thickness Tolerance and Practical Choice

Normal PCB thickness tolerance stands at about ±10%. In connector-sensitive or controlled impedance applications, more stringent tolerances may be needed to support electrical and mechanical consistency.

The process of choosing the correct PCB thickness must be based on an organized selection. The engineers are expected to analyze the mechanical limits and the application environment and then analyze electrical requirements like the impedance and current limits. Reviews should also be made on thermal requirements, enclosure constraints, and connector specification. In the absence of special requirements, the usual thickness of 1.6 mm is generally less difficult to manufacture and less expensive.

PCB thickness is not simply a dimensional specification—it is a core design parameter that influences structural integrity, electrical performance, thermal behavior, and manufacturing efficiency. From ultra-thin wearable electronics to heavy-duty power systems, the correct thickness ensures reliability and cost control.

At PCBCart, we encourage early-stage stack-up consultation to align thickness selection with performance goals and fabrication capabilities. A well-planned PCB thickness strategy reduces redesign risk, shortens lead time, and supports long-term product success.